Study of Walters 143 Manuscript of the Roman de la Rose

Garrett Shields

San Jose State University

Prof. Elizabeth Wrenn-Estes

LIBR 280-12

March 5, 2012

Table of Contents

Introduction

Context

Authors

Incipit

Explicit

Colophon

Size

Binding

Writing Support

Collation and Layout

Scripts, Scribes, and Ink

Rubrication

Decoration and Painting

Illumination

Summary

References

Introduction

The

Roman

de la Rose,

or translated from the French, the Romance

of the Rose

is an important work of medieval literature as well as rich source

for those involved in manuscript studies. Depending on sources,

there are between 200 and 300 different manuscripts available of

Roman

de la Rose

ranging from the 13th

to 15th

centuries, including one with critical essays, “possibly

the first truly ''critical edition" of a medieval vernacular

text ever produced (Brownlee,

1992, p. 1). Originally a French work, it quickly spread to

influence other works of the time. It was a secular work that found

its way into monasteries. (That heritage will be seen below in some

additional illustrations made to this particular manuscript.)

Roman

de la Rose

can be controversial and divisive, which may account for its

popularity. This comes from the fact that it was written by two

authors, working independently from one another with different

motivations at different times. The first 4058

lines were

written by Guillaume de Lorris around 1230, and Jean de Meun

constructed a second part consisting of 17,724 lines that was

finished around 1275.

Walters

(2012) describes Guillaume de Lorris's part of Roman

de la Rose

is an “idealized conception of the love quest.” It is a poem in

which a young man, stricken by an arrow from the God of Love, pursues

his love Rose who is walled off. After stealing a kiss, his Rose is

placed under further protection and de Lorris' part of the Roman

concludes.

In this part, Rose is clearly an allegory for sexuality, purity, and

fragility, something that McCaffrey describes as an “ idealized

version of the love object.”

This

idealization is central to de Lorris's contribution to the Roman.

The controversy and much interest in this work is created by the

juxtaposition of Jean de Meun's additional lines in which our

protagonist is “more courtly, more extreme, and more foolish” and

characters are far less idealized (McCaffrey). The story concludes

with “a bawdy account of the plucking of the Rose, achieved through

deception” (Walters).

The

Roman

de la Rose,

existing prolifically in manuscripts, is an important subject for

manuscript studies. Walters 143 Roman

de la Rose,

examined here, is one of perhaps 20 Roman

manuscripts believed to be illustrated by Richard and Jeanne de

Montbaston. Those illustrations, along with the work of the unknown

scribe will be examined more fully below. Hopefully, part of what

makes the Roman

de la Rose

so long-lasting and complex will be conveyed through this

examination.

This

sentiment may be evidenced in the manuscript itself, by a few

alterations and additions that made their way in over the centuries.

On 69v, shown below on the left, a painting has been altered to show

what appears to be a Dominican friar embracing a woman in a romantic

way. Further, on 72v, a dog dressed as a Dominican friar leading a

pack of dogs.

This

sentiment may be evidenced in the manuscript itself, by a few

alterations and additions that made their way in over the centuries.

On 69v, shown below on the left, a painting has been altered to show

what appears to be a Dominican friar embracing a woman in a romantic

way. Further, on 72v, a dog dressed as a Dominican friar leading a

pack of dogs.

Context

In

the period of about fifty years that the Roman

de la Rose

was written France was in the midst of the Crusades, but it was

otherwise, under the rule of Louis IX the political climate was calm

if not liturgical; after all Louis IX becomes Saint Louis. Guillaume

de Lorris wrote in this time, and perhaps his romantic and chaste

love story is a reflection of the time in which he lived.

After

Louis IX, Phillip III came into power, was quickly killed in the

Crusades, and was succeeded by Phillip IV. Around this time, Jean de

Meun was authoring his bawdier continuation to Roman

de la Rose.

This could be seen as a reaction to the religious overtones

permeating much of the country's affairs. That de Meun introduces a

satirical element into this story, and that he undermines some of the

romantic aspects of de Lorris's previous work could indicate that

there was room for a different way of thinking in France.

This

sentiment may be evidenced in the manuscript itself, by a few

alterations and additions that made their way in over the centuries.

On 69v, shown below on the left, a painting has been altered to show

what appears to be a Dominican friar embracing a woman in a romantic

way. Further, on 72v, a dog dressed as a Dominican friar leading a

pack of dogs.

This

sentiment may be evidenced in the manuscript itself, by a few

alterations and additions that made their way in over the centuries.

On 69v, shown below on the left, a painting has been altered to show

what appears to be a Dominican friar embracing a woman in a romantic

way. Further, on 72v, a dog dressed as a Dominican friar leading a

pack of dogs.

This anti-religious sentiment may have been added by

some satirical spirit similar to de Meun, but it assuredly shows that

this manuscript was read by several kinds of people. Perhaps that

lends credibility to fact that this manuscript is one of hundreds

that still exist of this text, that it has retained its popularity

throughout the centuries.

Authors

Not

much is known about about Guillaume de Lorris, but an inscription on

the opening flyleaf gives about as much information as anybody knows.

This translates,

roughly, to “The Romance of the Rose by Guillaume de Lorris started

and completed by Jean de Meun. Guillaume de Lorris died in 1260 and

Jean de Meun completed after 40 years. Guillaume de Lorris lived

during the reign of St. Louis and Jean de Meun under Philip the

Fair.”

Essentially,

the timeframe de Lorris wrote this in was known, but even his death

in 1260 is disputable. (Guillaume, 2011). The Roman de la Rose

provides little temporal context as well. The story is essentially

archetypal, a Genesis-type story that takes place in a dream, further

making a date of authorship complicated.

More

is known about Jean de Meun in comparison. He was believed to have

lived from around 1240 – 1305, and his writing of his part of the

Roman, with its vernacular

context, vulgarities, and satirical qualities suggest that it was

written in the latter part of the 13th

century.

There

appears to be no Incipit, or text marking by the scribe “here

begins” as Alvin (1991) remarks is commonplace amongst manuscripts

in this period (p. 221). The first page can be seen here, ornately

illustrated. Perhaps that is one reason for the lack of incipit;

with a work so popular and well known, it was perhaps deemed

unnecessary.

Explicit

Similarly,

there is no Explicit or

Finit, presumably for

the same reasons.

Colophon

After

examining the manuscript, it appears there is no colophon present in

this work either. Clemens and Graham (2007) note that “only a

relatively small proportion of medieval manuscripts include such

colophons,” and were “more popular at certain times and places:

for example, among early medieval Irish and Spanish scribes and among

Italian humanist scribes” (p.117). Since this manuscript of Roman

de la Rose

is neither, it is not unusual for it to be lacking a colophon.

Size

The

manuscript measures 300mm, or almost one foot in height, and

measuring from the center of the spine to the edge is 235mm, or about

9.25 inches. The parchment itself measures slightly smaller, of

course, being 289mm tall and 205mm wide.

Binding

Within

each of the columns, there are two more lines that separate the first

letter of each word with the rest of the line. There is also

horizontal line in brown ink to delineate a header, but there is no

distinction for a bottom border. Horizontal lines are also used for

each line of the poem, but do not extend beyond.

Textualis,

which was the most common script in France at this time for

manuscripts, is used throughout Roman de la Rose. One scribe is believed to have

created this manuscript originally, due to the consistency in lettering a color. A brown ink was

used by this scribe, and the few irregularities are marked in a black

ink, added by a different scribe. There are a few instances of this,

most notably on folio 143—pictured previously--where the page tore

away vertically and parchment was reattached with writing by a

different scribe. Another instance of this is seen on 50r, pictured above, where corrections were made with black ink at a later time by

a different scribe.

Textualis,

which was the most common script in France at this time for

manuscripts, is used throughout Roman de la Rose. One scribe is believed to have

created this manuscript originally, due to the consistency in lettering a color. A brown ink was

used by this scribe, and the few irregularities are marked in a black

ink, added by a different scribe. There are a few instances of this,

most notably on folio 143—pictured previously--where the page tore

away vertically and parchment was reattached with writing by a

different scribe. Another instance of this is seen on 50r, pictured above, where corrections were made with black ink at a later time by

a different scribe.

Binding

Unfortunately,

I was not able to handle this manuscript in person. There do

not appear to exist any images of the binding or anything other than

scanned pages. Because of this, I am forced to rely on the

description as listed from Roman de la Rose

(romandelarose.org), which follows:

Brown leather,

probably sheepskin, rectangular boards, five raised bands on spine

(partially recessed), headband and tailband of white thread. Front

and back covers have simple frame consisting of single blind-tooled

fillet. Spine features gold-tooled designs, now badly

faded/deteriorated and hard to make out, in the first and third

through sixth compartments. At both top and bottom of spine, two

simple blind-stamped lines. In second compartment, red leather title

label with two gold-tooled lines each at top and bottom of

compartment, and the following title: LE ROMAN / DE / LA ROSE. Fore,

top, and bottom edges marbled in red, now quite faded. One paper

flyleaf each, front and back; other half of each bifolium used as

pastedown in front and back.

Writing

Support

This

manuscript of Roman is

written on parchment, which is common for the time it was written.

The parchment is in good condition, given its age, but it is browning

and has a few signs of wear. On the first page, there are wormholes

that have been repaired, but there are also small tears in the paste

down, exhibited below.

The

other large compromise to the structural integrity of this manuscript

is the rip that runs the length in folio 143 that has been lost, and

replaced by a later scribe, the only evidence of a different scribe

in the manuscript.

Collation and Layout

The

Walters 143 manuscript is collated into eight quires, each consisting

of eight leaves. The layout is consistent, in a light brown ink.

There are 8 vertical lines—shown below, on a particularly prominent

page—that divide the page into two columns of text.

Scripts, Scribes, and Ink

Textualis,

which was the most common script in France at this time for

manuscripts, is used throughout Roman de la Rose. One scribe is believed to have

created this manuscript originally, due to the consistency in lettering a color. A brown ink was

used by this scribe, and the few irregularities are marked in a black

ink, added by a different scribe. There are a few instances of this,

most notably on folio 143—pictured previously--where the page tore

away vertically and parchment was reattached with writing by a

different scribe. Another instance of this is seen on 50r, pictured above, where corrections were made with black ink at a later time by

a different scribe.

Textualis,

which was the most common script in France at this time for

manuscripts, is used throughout Roman de la Rose. One scribe is believed to have

created this manuscript originally, due to the consistency in lettering a color. A brown ink was

used by this scribe, and the few irregularities are marked in a black

ink, added by a different scribe. There are a few instances of this,

most notably on folio 143—pictured previously--where the page tore

away vertically and parchment was reattached with writing by a

different scribe. Another instance of this is seen on 50r, pictured above, where corrections were made with black ink at a later time by

a different scribe.

In

addition, there are strikethoughs across entire columns on 30v and

31r, but it does not seem clear why the original scribe did this, or

if he were the one to do it.

Rubrication

The

rubricator of this manuscript appears to be the same scribe to worked

on the rest of the manuscript, and in tradition, red ink has been

used to mark changes in the speaker or textual divisions as seen

below. The ink has maintained its color pretty well throughout time,

compared to others that seem to fade and become indistinguishable

from the main script (Clemens & Graham, 2007, p. 25).

Decoration

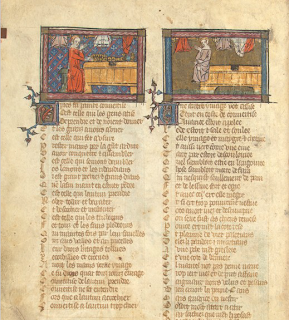

There

is much ornamentation throughout the Roman de la Rose,

but not more so than on folio 1r, shown here.

Several different color inks are used including red, blue, black, white, green, purple, and orange. This piece contains ornate work, representations of scenes in the story, portraits of characters bordering the script and wrapped in vines. It is very decorative, and these flourishes are present throughout the text as well. There are 41 more illustrations like this throughout the manuscript, but they are smaller pieces, like the one pictured below.

Illumination

After

checking all of the painting, decoration, and script, it is

determined that this manuscript contains no illumination as it would

surely be evident in some of the ornate painting like on folio 1r if

it were there.

Summary

The

Walters 143 Roman de la Rose

is an impressively complete manuscript from the 13th

century. It is a very helpful study for one beginning to examine

manuscripts because it was created in such a singular fashion, in

scribe, script, and format. This uniformity is enlivened by the

disparities that occur, like the odd strikethroughs, the torn

parchment and amended page, and the corrections made by another

scribe in a different ink. The damage done to the manuscript is

light, considering its age, with several of the paintings and details

retaining much of their luster. This manuscript is not only helpful

to the student, but the appreciator of history and fine art.

References

Arvin, L. (1991). Scribes, script and books:The book arts from

antiquity to the renaissance. Chicago,

IL: American Library Association.

Brownlee, K. (1992). Rethinking The Romance of the Rose :Text,

image, reception [eBook version]. Retrieved from

http://www.ebscohost.com

Clemens, R., & Graham, T. (2007). Introduction to manuscript

studies. Ithaca, New York:

Cornell University Press.

Guillaume de Lorris. (2011). Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th

Edition, 1. Retrieved from http://www.ebscohost.com

McCaffrey, P. (1999). Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Muen: Narcissus

and Pygmalion. Romanic Review, 90(4), 435. Retrieved

from http://www.ebscohost.com

Walters, L. (2012). History and summary of the text. Roman de la

Rose. Retrieved from

http://romandelarose.org/#rose

No comments:

Post a Comment